Over at his blog, Hurtado summarizes Tom Wright’s review of Pauline scholarship in what seems to be the first post of two on the state of Pauline scholarship. The following post will summarize Douglas Campbell’s approach to Paul, Duke’s own most recent thorough investigations into the question of Paul and Justification with a fresh, yet some might find odd, reading of Romans 1-3. The review of Wright is certainly worth a quick read, and we look forward to a helpful summary of Campbell (especially those of us who haven’t made our way through the entirety of his door-stop-of-a-tome, The Deliverance of God). Check it out here.

Over at his blog, Hurtado summarizes Tom Wright’s review of Pauline scholarship in what seems to be the first post of two on the state of Pauline scholarship. The following post will summarize Douglas Campbell’s approach to Paul, Duke’s own most recent thorough investigations into the question of Paul and Justification with a fresh, yet some might find odd, reading of Romans 1-3. The review of Wright is certainly worth a quick read, and we look forward to a helpful summary of Campbell (especially those of us who haven’t made our way through the entirety of his door-stop-of-a-tome, The Deliverance of God). Check it out here.

Good link on the Rules of Jewish Hermeneutics

Curious about how Rabbinic hermeneutics works? This is a good resource for an entry into how Jewish hermeneutics works. Click on “Rules of Jewish Hermeneutics” to check out the website. It was put together by HIllel Ben David (Greg Killian). Check it out.

Curious about how Rabbinic hermeneutics works? This is a good resource for an entry into how Jewish hermeneutics works. Click on “Rules of Jewish Hermeneutics” to check out the website. It was put together by HIllel Ben David (Greg Killian). Check it out.

Resurrection? Bringing the Blog back to Life

Happy Easter to all! Christos Anesti!

Happy Easter to all! Christos Anesti!

It has been just over two months since our last post here on The Time Has Been Shortened, and after friends have pestered us about whether or not we are going to continue blogging, we feel that it is time for an explanation. Many of us are very busy in life right now as grad students. With some of us having two or more jobs, pastoring, grad work, having children, etc. it has been very difficult to maintain a blog on biblical studies. We have been discussing this and have decided to incorporate more of our current projects and interests from our classes, especially major paper topics that we find interesting or worth sharing.

Also we have had many requests to finish the New Testament portion of our interview series I began entitled: “Monotheism and the Bible: Origins, Issues, and the Status Quaestionis.” The interviews with Nathan McDonald and Michael Heiser in the “Monotheism and the Hebrew Bible” section were well received. They have been found to be helpful for people interested in receiving a basic introduction to the contours of the present scholarly conversation regarding “monotheism” and the Ancient Israelite religion (whether variegated or monolithic) represented in the Hebrew Bible.

What still remains is to complete the interviews regarding the nature of Christology and Monotheism that is represented in the New Testament. The interviewees chosen for this specific topic were chosen based on their experience in the field: Larry Hurtado, who has written and taught for many years on the topic, and James McGrath, whose 2009 monograph “The Only True God: Early Christian Monotheism in its Jewish Context” sparked a lively discussion between the two scholars highlighting important points of divergence in the wider conversation regarding the nature of early Christian monotheism and christology. It will be genuinely interesting to pick up this conversation where it left off to see if there are any further nuances the scholars would like to share regarding this heated topic of discussion. My hope is that both will still graciously participate, even though the interview series had been put on hold for the semester.

“The Time Has Been Shortened” is happy to announce it’s resurrection on resurrection day. What better day to do it?

Monotheism and the Bible: Origins, Issues, and the Status Quaestionis – Hebrew Bible/OT Part 2

Second Interview of two in the “Monotheism and the Hebrew Bible” Series

Second Interview of two in the “Monotheism and the Hebrew Bible” Series

Interviewee: Dr. Michael S. Heiser

– Academic Editor, Logos Bible Software, Bellingham, WA

– Dissertation entitled “The Divine Council in Late Canonical and Non-Canonical Second Temple Jewish Literature”

– Authors the blog entitled: “The Naked Bible: Biblical Theology, Stripped Bare of Denominational Confessions and Theological Systems”

1. How do we define “monotheism”?

It all depends. Is the question how do “we” (moderns) tend to define monotheism? Or, how we should define monotheism? Or how ancient Israelites defined monotheism? Moderns would define it as a belief in one God, but “belief in one God” is itself vague. That phrase probably means “belief that one God, and only one God, exists.” As Nathan MacDonald points out (in “Deuteronomy and the Meaning of Monotheism”), the term is a modern one (17th century) and so, therefore, would the definition be modern. I’ll still use the term since I live in the modern age (!) but I don’t care for the modern definition as someone who accepts the Judeo-Christian canon.

The biblical writers used the term elohim to refer to half a dozen figures or entities in the unseen spiritual world (Yahweh, the elohim of Yahweh’s council, “demons” [Deut 32:17], the disembodied human dead [1 Sam 28:13], and angels [at least I’d argue for that on the basis of the plural verb in Gen 35:7 and its referent point]). The fact that they do that should tell us loudly and clearly that that they did not associate the term elohim with a specific set of attributes. We do that reflexively as moderns—we use “g-o-d” thinking of the singular being we know as the God of the Bible. Consequently, we feel uncomfortable with other elohim no matter how clear the biblical text is in that regard. The biblical writer did not think about elohim the way we think of “g-o-d.” They did not presume that elohim spoke of specific attributes that might be shared equally between Yahweh and other entities called elohim. It would have been absurd to the biblical writer to suggest that dear, departed uncle Jehoshaphat and aunt Rivka were on an ontological par with Yahweh and the elohim of His council, or that the members of Yahweh’s council and the elohim of the nations were on par with Yahweh *simply because they were all elohim.” And yet this is precisely what is assumed when people argue about Israelite monotheism.

The most straightforward way to understand the biblical use of elohim is to divorce it from attribute ontology. Elohim is what I like to call a “place of residence” term. It doesn’t tell me what a thing is in terms of attributes; it tells me the proper domain of a thing. All elohim are members of the unseen spiritual world, their place of residence. In that realm there is rank, and hierarchy, and in the case of Yahweh, uniqueness in attribute ontology. Those concepts are conveyed by other words and descriptions, not the word elohim. Yahweh is an elohim, but no other elohim is Yahweh. Yahweh was not one among equals; he was what I like to call “species unique.” That is what the biblical writers believed, so that is how I’d “define” monotheism, even though the term is awkward because of the modern baggage. However, the thought behind the term—that Yahweh is utterly and eternally unique—remains completely intact.

2. In the text of the Hebrew Bible, do you see a progression or development to monotheism? If so, is that progression a development in kind or a development of degree (or both)?

No. I believe the biblical writers believed Yahweh was unique among all elohim. I don’t care if our modern term “monotheism” fits that or not – but as I noted in the last question, it fits the spirit of the term. I’m delivering a paper on why I reject the evolutionary idea *for the biblical writers* at the annual ETS meeting, so people can read that paper. I can’t reproduce it here. The paper will be available after ETS/SBL next week (David will include the link then to the paper). I think the view is at least in part based not on what we have in the Hebrew Bible, but from what people imagine once existed. I don’t like to speculate; I’d rather go with what’s there – the final form of the text. I tend to like to draw conclusions deriving from exegesis of what we’ve received rather than on speculative texts that don’t exist. And when it comes to what we do have, I think the evidence offered for the idea is pretty much read into the text on the basis of certain assumptions.

Aside from the writers, though, I think that among Israelites there was a wide diversity of opinion or belief at all periods about how to talk about God, the gods, and the unseen world. Lots of people who today would appropriate the label “Christian” don’t even agree on this, so how much more the ancient Israelites who didn’t have direct access to most of their Scriptures for most of their history? My view is that there was theological diversity here. The biblical writers were part of that diversity, and what they believed has been given to us in the text as we have it.

4. Is the distinction between “polytheism” and “henotheism” necessary or helpful?

It’s helpful in that henotheism is monarchic polytheism, but that doesn’t say enough, especially about Israelite belief (as it’s reflected in the text). Henotheism operates without forbidding praying or offering sacrifices to many gods; it requires only the recognition of a supreme deity. But a henotheist would not see the top deity as utterly unique in attributes; he was only at the top through an imagined conquest of the pantheon, or perhaps earthly popularity. That is why I don’t think it is an adequate term for what the biblical writers believed. I’d need to see textual evidence that the biblical writers thought Yahweh could be toppled, or that they believed other gods had the same set of attributes before I’d consider them henotheists. Monolatry is better—monolatry is the rejection of worship and sacrifice to any deity other than the supreme deity. The biblical writers were certainly that, but again, that doesn’t say enough. I believe they also believed in Yahweh’s uniqueness. In other words, the biblical writers weren’t just monolatrous; they had certain beliefs about Yahweh that mattered, too (the reason he was the deity that should be worshiped).

5. What major texts are central to your view and why?

Passages that contain elohim. My view is based on the usage of the term as the biblical writers use it. It’s no more complicated than that.

6. What major texts are the most problematic to your view and why?

I can’t think of any, but that’s because I don’t accept the standard meaning of elohim. I can’t figure out why the biblical writers’ own use of elohim has escaped attention. If they use it of more than one being, and the beings of which it is used are described with other terms as greater or lesser in attributes and rank, then elohim cannot be a term that has to do with one set of attributes.

7. What would be the top 3 books you would recommend to students interested in the study of characterizing the kind of theism in the Hebrew bible/OT and ancient Israelite religion?

This is tough, since my view of elohim seems to be an actual contribution (or at least Nicholas Wyatt seemed to suggest that when he heard a paper of mine back at ISBL in Edinburgh). I think MacDonald’s book (noted above – “Deuteronomy and the Meaning of ‘Monotheism’“) is pretty helpful (it was to me anyway). I can’t think of any that subject the consensus view to any serious questioning. I’d have lots of recommendations for the divine council and binitarian monotheism, but that seems outside the question.

Monotheism and the Bible: Origins, Issues, and the Status Quaestionis – Hebrew Bible/OT Part 1

FIrst Interview of two in the “Monotheism and the Hebrew Bible” Series

FIrst Interview of two in the “Monotheism and the Hebrew Bible” Series

Interviewee: Dr. Nathan MacDonald

– Reader in Old Testament at University of St. Andrews and Sofja-Kovalevskaja-Preis Team Leader, Georg-August Universität Göttingen

– Author of “Deuteronomy and the Meaning of ‘Monotheism’”

1. How do we define “monotheism”?

The dictionary definition of monotheism is “the belief that there is only one God”. So far so good, but this is where the difficulties begin, as we can see if we examine the different parts of the definition.

First, “the belief”. The focus on beliefs rather than practices is striking and suggests that the conceptuality of monotheism may better capture intellectual paradigms than the larger religious framework, which consists of more than beliefs. Practices and beliefs are linked in a complex manner, of course, but some of the evidence we have about ancient Israel is much more readily related to practice rather than belief.

Second, “there is”. The issue becomes primarily, if not entirely, one of ontology. Issues of response are marginalized, if not excluded entirely. These issues of response are of much greater weight for the ancient authors and editors of the Old Testament.

Third, “one God”. What do we mean by a God, especially if we are going to deny that others exist? Is belief in other supernatural beings, such as angels or demons, not monotheistic? (Supernatural is itself a problematic category, of course).

Fourth, “only”. The “only” in such a definition is usually taken to mean the denial of the existence of other gods. Where this is not present, do we still have monotheism? (And if no, have we narrowed down our texts with what is merely a formal category?) How do we judge if such denials are rhetorical?

All of this suggests that monotheism is a remarkably difficult concept. That doesn’t mean barring its use as some have suggested – such strictures would be readily ignored anyhow! But in describing the beliefs and practices in the ancient Near East, including the Levant, we need to ensure we know what we are doing when we employ such categories, and most particularly ensure we don’t smuggle things into our description of ancient religions. In other words, the hermeneutical issues that circle around the monotheism debate are rather complex.

2. In the text of the Hebrew Bible, do you see a progression or development to monotheism? If so, is that progression a development in kind or a development of degree (or both)?

The question of progression or development is more naturally suited to a discussion of Israelite religious history, rather than the ‘text of the Hebrew Bible’ per se. The texts of the Hebrew Bible evidence an insistent monolatry, or call it monotheism if you wish. These take a variety of different forms, such that I have occasionally spoken of early Jewish monotheisms, a coinage that is meant to parallel the use of Judaisms in recent scholarship on the Second Temple period. Thus, the monotheism of Deutero-Isaiah and the priestly document look very different from one another, even if they stem from the late neo-Babylonian or early Persian period. This diversity only increases if we consider Jewish wisdom literature or Jewish apocalyptic. These are also arguably monotheistic, but quite different from Deutero-Isaiah and P. In this sense, I would like to speak of the variety of monotheism in the Hebrew Bible, rather than its progression or development.

3. (If yes to the previous question) Are there distinct periods in which you see these developments (a timeline of sorts) and how would you characterize or describe the shifts in thinking or praxis?

This sounds to my ears like a different issue: one relating to religious history. The biblical texts are some of the evidence one might utilize, but sits alongside archaeological finds, inscriptions, finds from Mesopotamia etc. The biblical text can provide some evidence of earlier beliefs and practices – this is perhaps what you were looking for in the previous question. By critical analysis earlier perceptions and ideas may be discernible behind the final monolatrous or, if you prefer, monotheistic perspective of the Hebrew Bible.

I do think there are noticeable shifts at certain periods, but these should not be over-exaggerated. In particular, there may be more continuity between practice and belief before and after the neo-Babylonian period (the “exile”). I also think that the kind of diversity that I see in the Persian period makes it difficult to construct timelines of the sort you request.

It makes most sense to work back from latest to earliest. I am persuaded by Larry Hurtado that the Maccabean revolt marks an important step in the consciousness of Jewish uniqueness vis-à-vis Greek and other Levantine religions. That is, there is a strong sense amongst Jews and non-Jews that Judaism is other, particularly in its aniconic practice and cultic devotion to one God. Earlier in the Second Temple period there is more willingness to relate YHWH to other chief deities, although programmatic aniconism and insistence on YHWH-alone devotion are already strong. The significant changes in this period probably relate to a growing scripturalization – including the move towards harmonization as consistent with the revelation of one deity – and the emphasis on YHWH as Torah giver. In the neo-Babylonian period and earlier there are monolatrous tendencies, but these do not result in the exclusion of other deities in the religious practice of some. For earlier periods we are more and more reliant on archaeological and comparative evidence. It seems likely that worship of YHWH and El predominated, though it is uncertain when they were seen as the same deity. There was probably a pantheon, though on a far small scale than could be found in Mesopotamia.

4. Is the distinction between “polytheism” and “henotheism” necessary or helpful?

Henotheism is a difficult term precisely because it has been used by a variety of people in a variety of ways. I would need to know what idea of henotheism was being deployed before determining if this could be helpfully distinguished from polytheism. It should be said, of course, that many issues have been raised about the application of the term polytheism. Not least of these, is that polytheism is an inner-monotheistic way of characterizing other religions and does not accord that well to what “polytheists” hold to be important about their practices and beliefs. Max Müller’s coinage of henotheism (“there is a god”, rather than “there is one god”) was a partial attempt to address this issue, though I think its success was decidedly limited.

5. What major texts are central to your view and why?

My own interests are in describing the religious practices and beliefs of biblical writers in the round. In that sense there is no text that is not important. In particular, I’d want to say that there may be dangers in focusing on only the classic texts, such as Deut 6.4; Isa 40-48; Deut 32.8-9; Judg 11; Ps 82. These are much discussed because they are complex and interesting texts with a fascinating history of research. Nevertheless, it is here that our definition of monotheism may have overly determined the material for analysis. Our definition focuses on particular issues, and so narrows down the texts we examine.

6. What major texts are the most problematic to your view and why?

Sorry, I don’t understand the question.

More seriously, one tries to work with models that integrate all the material. When other scholars raise problematic texts it is necessary to go back and see how they might fit, or how the models need to change. My speaking of early Jewish monotheisms is at least partially an attempt to recognize the complexity of the evidence with which we are presented. It seeks to offer a comprehensive model, without being reduced to a linear development.

7. What would be the top 3 books you would recommend to students interested in the study of characterizing the kind of theism in the Hebrew bible/OT and ancient Israelite religion?

Mark Smith – The Origins of Biblical Monotheism. Smith’s work is very widely informed, but also depends upon careful, close reading of biblical and non-biblical texts. The first few chapters of Origins I think are particularly important for the penetrating questions they ask. I’m a little hard pressed here to choose between it and God in Translation, which I think breaks significant new ground. For orientating students to the debate about monotheism Origins gets the vote with the encouragement to go on and read God in Translation.

Fritz Stolz – Einführung in den biblischen Monotheismus. Like Smith has a broad canvas which is especially helpful for those orientating themselves to this debate. I think his reflections on post-exilic monotheism at the end of the book point out where new work needs to be done. It would also be a good introduction to the world of German scholarship where so much important scholarship is to be found: I think of the early work in the 1980s that brought the subject of monotheism into the centre of academic discussion, as well as the work of the Fribourg School on iconography.

Benjamin Sommer – The Bodies of God and the World of Ancient Israel. A lengthy appendix provides a synthetic overview of monotheism in ancient Israel. Sommer reflects the influence of Yehezkel Kaufmann and so views the discussion rather differently from many other scholars. This would give students a sense of the different flavors of scholarship, which would be no bad thing. It might also encourage them to read Kaufmann who puts his finger on significant issues, even if his proposals were so often implausible.

New Upcoming Interview Series: “Monotheism and the Bible: Origins, Issues, and the Status Quaestionis”

Questions on the origins of monotheism, the nature of ancient Israelite religion(s), and debates over early christology in relation to monotheism have been the topic of much of biblical scholarship as of late. There has been much ink spilled over inquiries and proposals attempting to best characterize or understand the type of theism the earliest Israelites and the earliest Christians actually had. There are a great deal of incredibly interesting and paradigm-shifting studies out there but where do we begin? Those who are interested in looking into these questions from a historical-critical perspective may find themselves overwhelmed and possibly discouraged, especially when attempting to find what is worth reading and what isn’t. We are beginning a new interview series here at The Time Has Been Shortened to deal with precisely this problem.

Questions on the origins of monotheism, the nature of ancient Israelite religion(s), and debates over early christology in relation to monotheism have been the topic of much of biblical scholarship as of late. There has been much ink spilled over inquiries and proposals attempting to best characterize or understand the type of theism the earliest Israelites and the earliest Christians actually had. There are a great deal of incredibly interesting and paradigm-shifting studies out there but where do we begin? Those who are interested in looking into these questions from a historical-critical perspective may find themselves overwhelmed and possibly discouraged, especially when attempting to find what is worth reading and what isn’t. We are beginning a new interview series here at The Time Has Been Shortened to deal with precisely this problem.

The series is entitled “Monotheism and the Bible: Origins, Issues, and the Status Quaestionis“. We will be interviewing scholars who have written extensively and are considered authorities in their respective fields who will be giving us the status quaestionis (or the state of the investigation) regarding monotheism and the Hebrew Bible/Old Testament and in the complex relationship between Christology and Monotheism in the New Testament. The series will consist of four interviews: two interviews on Monotheism and the Hebrew Bible and two interviews on Christology and Monotheism in the New Testament. The interviews will be most likely split up into two parts each due to breadth of a few of the questions.

First two interviewees in the Hebrew Bible section are as follows:

– PhD in Theology, University of Durham; MA, University of Cambridge (Honorary); MPhil in Classical Hebrew Studies, University of Cambridge; BA (honors, 1st class), University of Cambridge

– Sofja-Kovalevskaja-Preis Team Leader, Georg-August Universität Göttingen

– Reader in Old Testament, St Mary’s College, University of St Andrews

– Author of “Deuteronomy and the Meaning of ‘Monotheism’” and “Not Bread Alone: The Uses of Food in the Old Testament”

______________________________

– PhD in Hebrew Bible and Semitic Studies, University of Wisconsin-Madison; MA in Hebrew and Semitics, University of Wisconsin-Madison; MA in Ancient History – Ancient Egypt and Syria-Palestine, University of Pennsylvania

– Academic Editor, Logos Bible Software, Bellingham, WA

– Dissertation entitled “The Divine Council in Late Canonical and Non-Canonical Second Temple Jewish Literature”

– Authors the blog entitled: “The Naked Bible: Biblical Theology, Stripped Bare of Denominational Confessions and Theological Systems”

Second two interviewees in the New Testament Section are as follows:

– PhD in Theology, University of Durham; BDiv (honors), University of London; Diploma in Religious Studies, University of Cambridge.

– Clarence L. Goodwin Chair in New Testament Language and Literature, Butler University

– Author of “The Only True God: Early Christian Monotheism in Its Jewish Context” and “John’s Apologetic Christology: Legitimation and Development in Johannine Christology”

– Authors the blog entitled: “Exploring Our Matrix”

______________________________

– PhD in New Testament, Case Western Reserve University; MA in New Testament, Trinity Evangelical Divinity School; BA in Biblical Studies, Central Bible College

– Professor Emeritus of New Testament Language, Literature, and Theology, University of Edinburgh

– Director of the Center for the Study of Christian Origins, University of Edinburgh

– Author of “Lord Jesus Christ: Devotion to Jesus in Earliest Christianity“, “How on Earth Did Jesus Become a God?: Historical Questions about Earliest Devotion to Jesus“, and “One God, One Lord: Early Christian Devotion and Ancient Jewish Monotheism”

– Authors the blog entitled “Larry Hurtado’s Blog: Comments on the New Testament and Early Christianity”

We are excited about the interview series. Be sure to subscribe to follow the conversation.

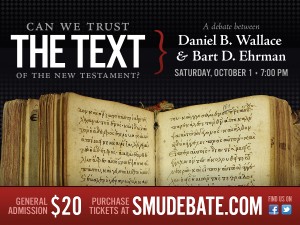

Largest Debate on the Historical Reliability of the New Testament Text in Recorded History?

Rob Marcelo with Friends of CSNTM (Center for the Study of New Testament Manuscripts) said via facebook today: “Tickets are continuing to sell fast, and this is now going to be the largest single debate on the Reliability of the text of the New Testament in recorded history! Make sure to pick up your tickets soon at www.smudebate.com”

Rob Marcelo with Friends of CSNTM (Center for the Study of New Testament Manuscripts) said via facebook today: “Tickets are continuing to sell fast, and this is now going to be the largest single debate on the Reliability of the text of the New Testament in recorded history! Make sure to pick up your tickets soon at www.smudebate.com”

So there you have it. This should be an interesting and lively debate between Bart D. Erhman of UNC Chapel Hill and Daniel B. Wallace of Dallas Theological Seminary. Though there have been debates similar to this one in this past, from a bit of insider information, there has been an inordinate amount of preparation for this debate on both sides. I think both scholars see this debate as a huge opportunity to bolster support for their agenda on both sides. The debate has garnered so much attention that the ticket sales have forced them to move locations to McFarlin Auditorium at SMU which has a seating capacity of 2,386 people. I’m excited about this and if you are in Dallas, Texas on October 1st and have any interest in New Testament studies, you should be there!

A New Blog on Teaching Koine Greek as a Living Language

I would like to give a warm welcome to one of my long time academic mentors and friends, Dr. Daniel R. Street, who has finally joined the blogging world. The blog, cleverly entitled “καὶ τὰ λοιπά“, meaning “and so on” or “et cetera” (etc), will be dedicated primarily to the teaching of Koine Greek as a living language, although he will be including posts on New Testament studies and cognate fields. Streett’s pedagogical methodology has been incredibly successful in the classroom at Criswell College as seen in the example of first year Greek students who have come out with a vocabulary triple that of a regular first year student at a normal university or seminary. He focuses on a strictly inductive approach focusing on attempting to create an immersive environment that engages the students on multiple levels.

I would like to give a warm welcome to one of my long time academic mentors and friends, Dr. Daniel R. Street, who has finally joined the blogging world. The blog, cleverly entitled “καὶ τὰ λοιπά“, meaning “and so on” or “et cetera” (etc), will be dedicated primarily to the teaching of Koine Greek as a living language, although he will be including posts on New Testament studies and cognate fields. Streett’s pedagogical methodology has been incredibly successful in the classroom at Criswell College as seen in the example of first year Greek students who have come out with a vocabulary triple that of a regular first year student at a normal university or seminary. He focuses on a strictly inductive approach focusing on attempting to create an immersive environment that engages the students on multiple levels.

There are many ways Streett attempts to create the immersive environment needed for the success of his method: giving simple commands and having students actively respond (stand, sit, walk around, pick up your book, etc), pointing and describing while students imitate, asking simple questions, describing pictures using Koine, etc. He has worked hard to find pictures that correspond to all the vocabulary learned in the class. Students will get together and have simple conversations only in Koine or write notes to each other either on paper or on Facebook. It is exciting to see this methodology taking off and the possibilities for it’s development and advancement in the near future.

Make sure and stop by the blog “καὶ τὰ λοιπά” and check it out. If you are interested in learning more about learning Greek as a living language or actually participating in or taking a class with Dr. Daniel R. Streett, feel free to email him at danstreett@gmail.com or contact Criswell College about signing up for classes for the following semester.

“The Time Has Been Shortened” Has Officially Joined the Biblioblog Community

![]() It is finally official! “The Time Has Been Shortened” is now a part of the Biblioblog community. Thanks goes out to Steve Caruso and Dan McClellan for their service at Biblioblog headquarters, we appreciate you guys. We look forward to engaging with such a rich and diverse collection of voices in the biblical studies blogging world. We will continue to post on topics of interest (mainly our interest that is) in biblical studies and related literature, book reviews, interaction with other biblical scholarship in general, and the occasional Interview Series. We also look forward to hearing feedback from others on the related issues or interpretations we may bring to the table on this blog. Thank you to the readers who already subscribe and look forward to many more in the future.

It is finally official! “The Time Has Been Shortened” is now a part of the Biblioblog community. Thanks goes out to Steve Caruso and Dan McClellan for their service at Biblioblog headquarters, we appreciate you guys. We look forward to engaging with such a rich and diverse collection of voices in the biblical studies blogging world. We will continue to post on topics of interest (mainly our interest that is) in biblical studies and related literature, book reviews, interaction with other biblical scholarship in general, and the occasional Interview Series. We also look forward to hearing feedback from others on the related issues or interpretations we may bring to the table on this blog. Thank you to the readers who already subscribe and look forward to many more in the future.

Jordan Lead Codices… Certainly Forgeries.

If you still are in question at the authenticity of the Jordan Lead Codices check out my friend Dan McClellan’s blog here. With the aid of other bibliobloggers, he helps expose much of the Elkington’s (those behind the “find”) fervent efforts to suppress the mounting evidence against the authenticity of the codices. It has been demonstrated by metallurgists that “… this is not characteristic of lead that has been buried”, referring to the fact that, and I quote the original transcript, “… it would be expected that the surface crust would be thicker and that there would be greater penetration of the metal leaving, at least, a pitted surface.” This transcript had been tampered with by the Elkingtons, removing this statement. It is time for them to be ignored and for any remaining hype to go away.

If you still are in question at the authenticity of the Jordan Lead Codices check out my friend Dan McClellan’s blog here. With the aid of other bibliobloggers, he helps expose much of the Elkington’s (those behind the “find”) fervent efforts to suppress the mounting evidence against the authenticity of the codices. It has been demonstrated by metallurgists that “… this is not characteristic of lead that has been buried”, referring to the fact that, and I quote the original transcript, “… it would be expected that the surface crust would be thicker and that there would be greater penetration of the metal leaving, at least, a pitted surface.” This transcript had been tampered with by the Elkingtons, removing this statement. It is time for them to be ignored and for any remaining hype to go away.