I recently had the opportunity to participate in an undergraduate Reacting Game on the Council of Nicaea at Duke University. This game was designed by David Henderson and Frank Kirkpatrick at Trinity College. The basic premise is that each student is given a character that was either present at the council or, because class sizes can be large, given a fictional character. The students are given personalized instruction regarding their character, including a biography, a theological agenda, and tips on how their character can best achieve victory points and win the game. As far as the game is concerned, students gain victory points by reaching certain objectives or can win outright if they meet a particular objective. As far as the course is concerned, students are graded based on their participation, on their written speeches that they turned in during the course of the game, and on their final paper they turn in at the end of class. Following almost half a semester of lectures, which gives a history of the Christian movement up to the beginning of the council, the game begins and lasts for three weeks.

I recently had the opportunity to participate in an undergraduate Reacting Game on the Council of Nicaea at Duke University. This game was designed by David Henderson and Frank Kirkpatrick at Trinity College. The basic premise is that each student is given a character that was either present at the council or, because class sizes can be large, given a fictional character. The students are given personalized instruction regarding their character, including a biography, a theological agenda, and tips on how their character can best achieve victory points and win the game. As far as the game is concerned, students gain victory points by reaching certain objectives or can win outright if they meet a particular objective. As far as the course is concerned, students are graded based on their participation, on their written speeches that they turned in during the course of the game, and on their final paper they turn in at the end of class. Following almost half a semester of lectures, which gives a history of the Christian movement up to the beginning of the council, the game begins and lasts for three weeks.

Having never experienced such a pedagogical apparatus, I was uncertain about what to expect. In the end, I had a blast and learned more about the council than I did during the first time I learned about this period (lecture style).

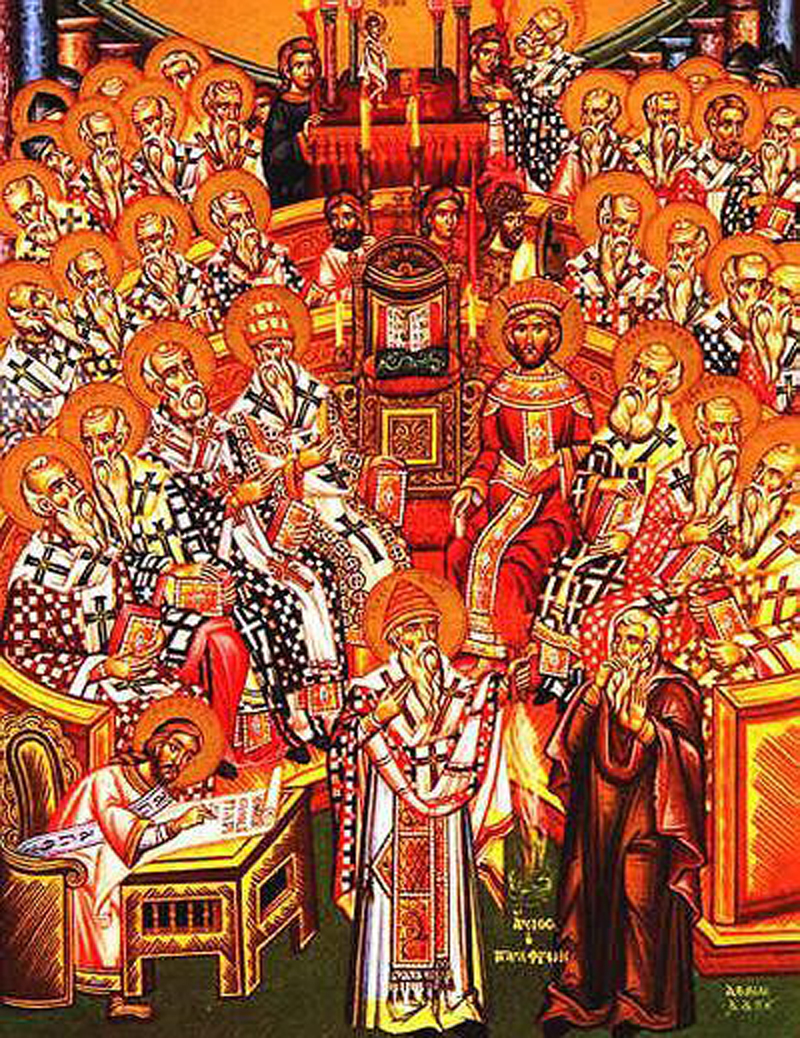

What I appreciate most about this teaching style is that it incisively portrays the political atmosphere of the historical council. In other words, with this pedagogy, the professor is not able to teach about the Council of Nicaea as if the results of the council reflected merely the pure and holy interpretations of Scripture. Indeed, reenacting the Nicaean Council problematized this conclusion on so many levels.

Because the class was so large, there were two councils playing at the same time. In the northern council, the Arian faction succeeded in writing a very Arian creed, while Athanasius was eventually excommunicated from the council. In the southern council, a more “orthodox” leaning creed won the day, while Arius bemoaned how unfair the entire council was. (Neither Arius nor Athanasius had voting power at the beginning of the council. They had to be ordained as bishops before they could vote and the southern Arius failed to do this, while the northern Arius was ordained by the second class session.) The southern Arius’ cries of foul play were justified, as he was completely marginalized by Ossius (Constantine’s favored bishop, who was of the “orthodox” persuasion), who limited Arius’ speaking time and readily dismissed his arguments (many of which were quite cogent).

In the southern council, the Gospel of John was rejected for the Gospel of Mary, a canon stating that women could hold ecclesial offices was ratified, and the date of Easter was synced with the Jewish Passover.

The political landscape of this council was an evolving matrix of power and monetary grabs, bribes, threats, aspersions, and falsehoods. On numerous occasions, the piety of bishops was unveiled to reveal sanctimonious actions and mischievous intents. Although ulterior motives were discovered, there were occasions when the bishop’s duplicity was victorious in pushing his agenda into the creed or solidifying it as a canon.

The politicking was not isolated to class time, as members of the councils engaged in secret emails, scurrilous tweets, and surreptitious meetings. The northern council was particularly active outside of class, as Constantine, Athanasius, and others bought lunch for certain bishops in order to persuade them to vote a certain way. Tweets and emails were often forged in hopes of maligning other characters.

From a pedagogical standpoint, such a learning environment forced the students to learn the agendas of all the other characters; after all, they needed to make allies, know who they might need to persuade and how to persuade them, and know how to argue against their opponents. In addition, the students had to recognize that while one person might oppose them on one issue, he might be their biggest ally on another; enemies quickly became friends and friends, enemies. This ever-changing environment demanded that students learn the material inside and out.

Each class period was full of students giving speeches to promote their agendas, counter speeches, and many impromptu dialogues where characters were digging dip into their knowledge of scripture and appealing to the desires of friends (and sometimes foes) to win the debate and get their objectives put into the creed or ratified as a canon. There were many occasions where these undergraduates impressed me with how well they knew the appropriate information and could negotiate the situations on the fly.

From my perspective (a graduate student who participated but also observed for pedagogical worth), I would say this game was a success. The students displayed an active knowledge of the material and synthesized and applied that knowledge throughout the game. The students also had to turn in their speeches to the professor, as well as write a paper, so the professor will have a better idea about how well they did. But if there is anything these students take away from this class, they will certainly walk away with the realization that the Council of Nicaea was dictated more by politics, influence, and power than by the hand of God. Personally, rather than the calm and heavenly image of the Council posted above, it seems that a more likely image would be a bit more contentious.

While it is difficult for us today to think of salvation in terms that exclude Jesus’ life, death, or resurrection, there appears to have been some Christian groups that understood God’s plan of salvation apart from these events of Jesus’ earthly existence. In what follows I want to look at three second-century texts that speak of conversion without mentioning Jesus’ life, death, or resurrection.

While it is difficult for us today to think of salvation in terms that exclude Jesus’ life, death, or resurrection, there appears to have been some Christian groups that understood God’s plan of salvation apart from these events of Jesus’ earthly existence. In what follows I want to look at three second-century texts that speak of conversion without mentioning Jesus’ life, death, or resurrection.