The latest book from my doctoral advisor, Andrei A. Orlov, has been published and is now available for purchase with T & T Clark, entitled, The Glory of the Invisible God: Two Powers in Heaven Traditions and Early Christology. I had the privilege of editing this volume while working as Dr. Orlov’s research assistant, so I am excited to finally see it in print. For those of you who are interested in early Judaism and Christian origins, you will likely enjoy this fascinating contribution to the scholarly conversations surrounding the development of earliest Christology. This book is situated squarely within the ongoing conversations regarding the nature and origins of early Christology. Dr. Orlov describes the work as follows:

“The book explores transferals of the theophanic attributes of the divine glory from God to Jesus in the synoptic gospels through the spectacles of the so-called “two powers in heaven traditions.” The application of the two powers terminology to early Christian texts is regarded by some as an anachronistic application that could distort the intended original meaning of these sources. Yet, the study argues that such a move provides a novel methodological framework that enables a better understanding of the theophanic setting crucial for shaping early Christology. The terminology of “power” can be seen as an especially helpful provisional category for exploring early Jewish and Christian theophanies, where the deity appears with the second mediatorial figure. In these accounts the exact status of the second person who appears along with the deity often remains uncertain, and it is difficult to establish whether he represents a divine, angelic, or corporeal entity.

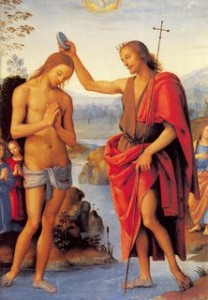

The book offers a close analysis of the earliest Christian theophanies attested in the baptism and transfiguration stories of the synoptic gospels. The study demonstrates that Jesus’ divine identity was gradually developed in the New Testament materials through his endowment with God’s theophanic attributes. Such endowment is clearly demonstrated in the account of Jesus’ transfiguration, where Jesus’ metamorphosis is enveloped in the features of the visual paradigm as well as the details of its conceptual counterpart—the aural trend applied in the depiction of God’s voice. The study suggests that the earliest Christology emerges from this creative tension of the ocularcentric and aural theophanic molds, in which the deity steadily abandons its corporeal profile in order to release the symbolic space for the new guardian, who from then on becomes the image and the glory of the invisible God.”

In The Glory of the Invisible God, Orlov not only provides us with thought-provoking treatments of these all too familiar gospel stories, but promises to be an engaging dialogue partner in the ongoing pursuit of the origins of earliest Christology. Those who are interested in the book who will be attending the 2019 Annual Meeting of the Society of Biblical Literature in San Diego will be able to purchase it at the conference discounted rate at the T & T Clark booth in the convention center. For all others you can purchase the book through T & T Clark here.

Tolle lege!